Sherlock Holmes Escape Books

Three Adventures: The London Waterworks, The Two Flying Scotsmen, and The Train of the Dead1

This isn’t really a Beholder project, because the publishers Ammonite made them... but, as Ormond Sacker, I was commissioned to help create some of the books in this series for them.

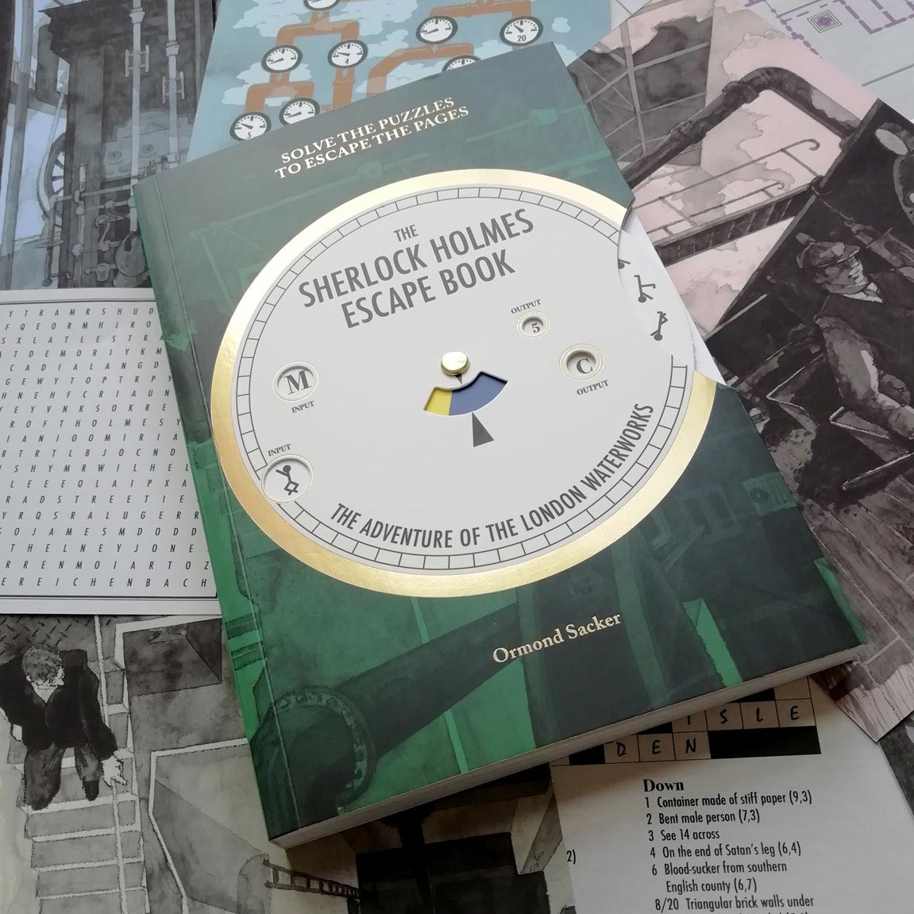

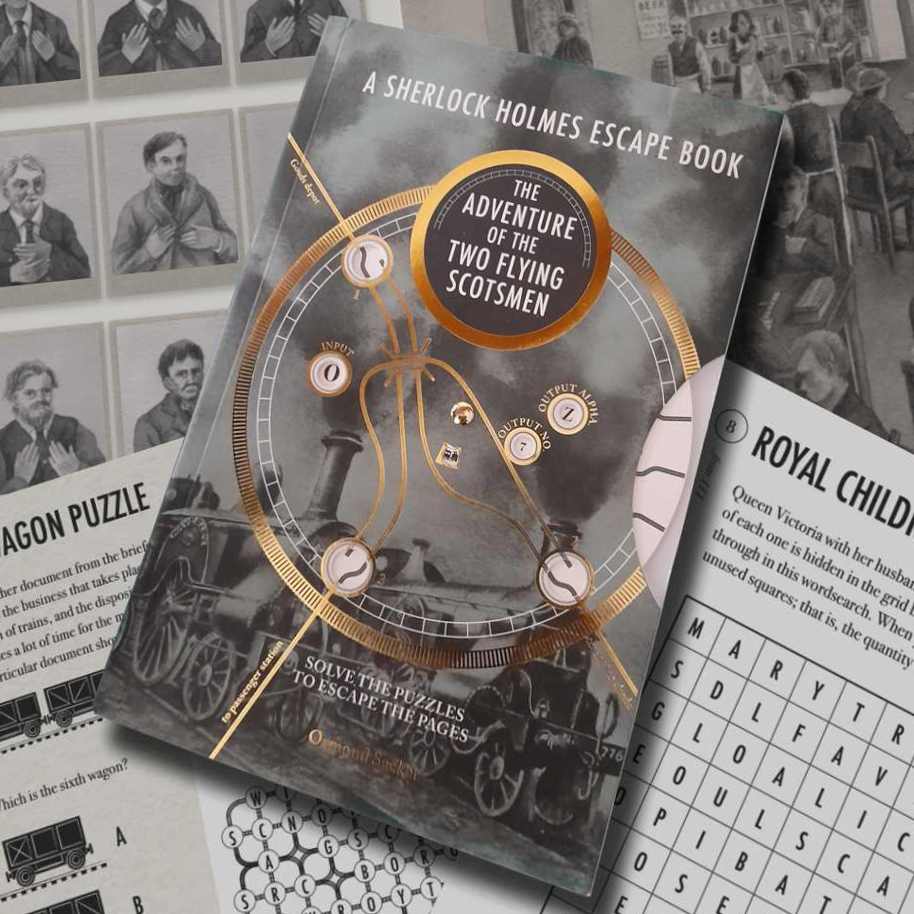

These are choose-your-own-path adventure-style puzzle escape books, in which your answers to the puzzles determine your route through (and, eventually, out of) the book. The evocative full-page illustrations are by Tobias Willa and Chien-wei Yu, all the supporting graphics are by Ammonite’s designer Robin Shields. We even snuck an extra Sherlockian short story by Viv Croot in the Waterworks one if you are observant enough to find it. The books feature a volvelle (in effect, a code-wheel) on their covers.

Unlike Planetarium, progression through the story does depend on your solutions to the puzzles — but hints and the complete2 solutions are provided at the back of the books if you get stuck.

The Waterworks adventure was published in the UK in July 2019, and the Two Flying Scotsmen in November 2024. The Train of the Dead is due out in November 2025 (and now available for pre-order, if that’s the sort of thing you do). If you want it you can wander into your favourite (ideally independent) bookshop and ask for them. Alternatively, buy online:

The Adventure of the London Waterworks

The Adventure of the Two Flying Scotsmen

The Adventure of the Train of the Dead

(publication date: Nov 2025... some online sites won’t have it yet)

As part of the research for Waterworks I spent time with some of the excellent people and engines that are to be found in London’s great little Museum of Water & Steam at Kew Bridge, because I used their site — formerly the Grand Junction Water Works pumping station — as the setting of the main events in the book. For the Two Flying Scotsmen I benefited from the helpfulness of the librarians at the National Railway Museum in York, and (less obviously) the volunteer archivist at Easton Lodge.

If English isn’t your first language, the Adventure of the London Waterworks is available in French, Spanish, German, Dutch, and Greek editions — so you might be able to find a copy via your own local bookshop even if you’re not in the Anglosphere. The translation effort required to convert a text like this out of its original English, preserving both the explicit and hidden word puzzles’ payloads, is remarkable. It is arguably more difficult to translate the puzzles well than it is to create them in the first place, because the puzzle-writer is working with fewer constraints. I wasn’t involved with the translation effort, of course, but I did applaud it by giving a presentation to current students of translation in the Languages department of Royal Holloway, University of London (where I work part-time, albeit in a different department). I showed how the professional translators overcame some of the specific challenges presented by the original book. For people wondering where the limits of machine translation lie (which obviously concerns students looking to enter a career in such a field), this was a playful example of how translation through multiple levels of context still requires a creative human translator.

1 For the record, I much preferred the more accurate title The Adventure of the London Necropolis, but the publisher gets to choose this sort of thing; ultimately, it’s their book. ↑

2 Well, almost complete. There’s one puzzle whose workings I wouldn’t let them fully reveal. ↑